Building the Washington Monument

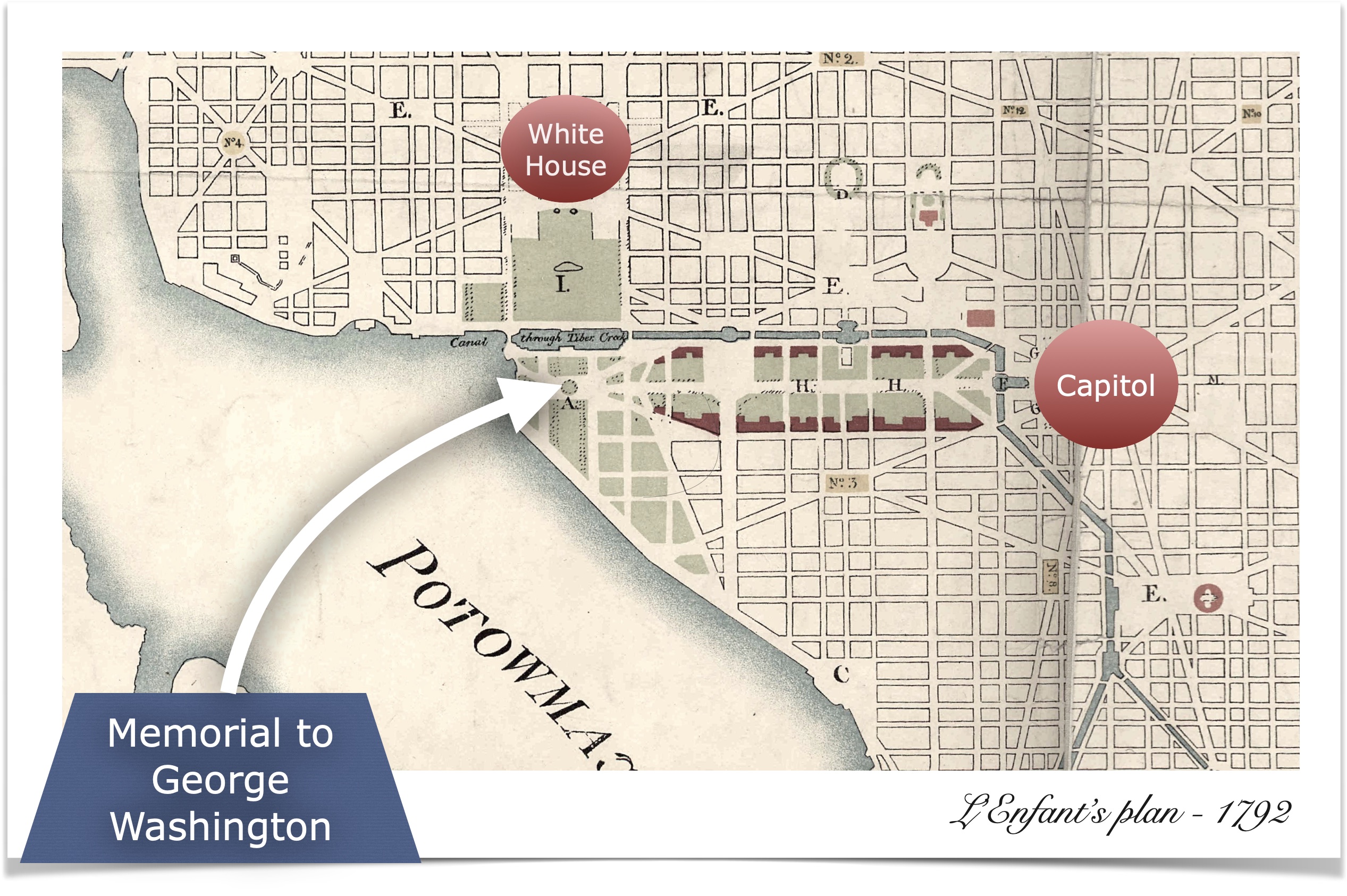

Pierre L’Enfant, the French artist who was hired to design a new capital city, included in his design a spot for an “equestrian” monument to George Washington. The spot he chose was one that could be seen from both the new Capitol and from the President’s House.

In 1832, the U.S. Congress commissioned sculptor Horatio Greenough to create a memorial to George Washington for the Rotunda of the Capitol. Upon completion in 1841, the statue was placed in the center of the Capitol Rotunda. While some appreciated Greenough’s attempt to create a classical masterpiece, others rejected an inappropriately dressed Washington. Two years later the sculpture was moved outside, where it remained for 60 years.

In 1908 Greenhough’s statue was moved to the Smithsonian.

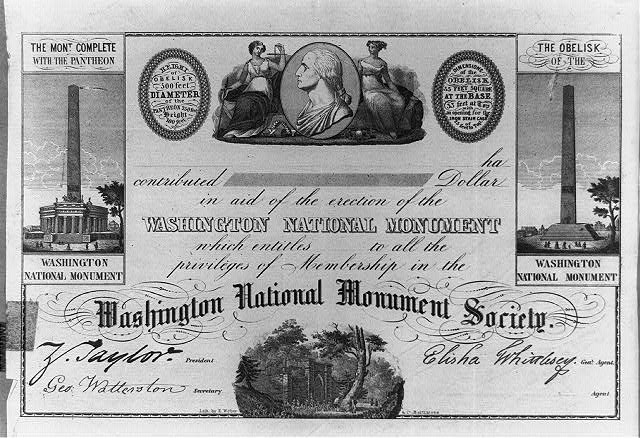

But Greenhough’s statue was not appropriate for the site that L’Enfant had identified for a memorial to George Washington. Frustrated with the lack of progress on a memorial on that site, a number of prominent citizens took matters into their own hands and created the Washington National Monument Society. Their objective was to raise money for a memorial specifically designed for the site L’Enfant had designated for the memorial.

In 1836 the Society held a nationwide contest for the design of the monument.

The winning design was by Robert Mills. It featured an interior column 600 feet tall, surrounded by a 150 foot high colonnade. On top of the colonnade would be sculptures of George Washington and other heroes of the Revolution. A steam-powered elevator would take visitors to the top of the 600 foot column.

From the outset, the Society had trouble collecting money. By 1838, it had only $28,000 for a project whose estimated cost was about $1,000,000 (about $28 million in today’s dollars). But by 1848, it had $87,000 on hand—enough, it was felt, to start work and hope for the best.

Groundbreaking

On July 4th, 1848 President James K. Polk presided over the ceremonial groundbreaking. Abraham Lincoln then serving his first and only term as a Representative from Illinois was in attendance as well as Dolley Madison, widow of President James Madison, and Elizabeth Hamilton, widow of Alexander Hamilton.

But the Society needed to raise more money. The society put collection boxes across the country—at government offices, hotels, fairs, churches, election sites, and the monument itself. It offered souvenirs, such as certificates signed by the President and other VIPs.

And, to save money, the society dropped the idea of a colonnade around the base of the obelisk.

The marble the society used for the outer layer must have come from one of the lowest bidders. It proved to be what would later be called “alum marble” because it crumbled so easily.

Today, for example, the corners of the monument have long since been replaced by new, whiter marble up the first 10 feet or so, the old material being damaged by erosion–and more relic-hunters. There are also scattered replacements further up to 150 feet, after which no replacements were needed.

During the 2000 restoration, there were piles of old society marble taken down and stored behind the scenes. One could pick up a lump and crumble it like cheese.

The Washington National Monument Society did the best it could on a shoestring budget. Despite later repairs, the basic structure was sound—indeed, it is still there today. In mid-December 1854, however, the society had to announce that work would cease. It had spent $230,000 and raised the column to 152 feet. In 1855, Congress debated appropriating $200,000 for the monument to get things started again, but in that year the society was taken over by the American Party, better known as the Know-Nothings. (When asked about their activities, they would reply, “I know nothing.”) The party was a brief successful nativist movement in the mid-1850s that did not like Catholics and thought that the Pope wanted to control America. Ironically, they sometimes called themselves Native Americans.

After this, almost no one wanted to contribute anything. The Know-Nothings ended up using rejected marble lying about the grounds and so added a total of three feet, three inches to the monument. The original society regained control in 1858.

In 1859, a little-known episode in the monument’s history showed that the nation’s women refused to sit on the sidelines.

Several women founded the Ladies Washington National Monument Society. The Ladies group was created in Chicago, sometime in September, appropriately enough at the Masonic National Convention. A Mrs. Finlay M. King of New York was elected the president, and Mrs. Anna M. Cosby of Washington, D.C., became the secretary.

All the officers, in fact, were women. Perhaps they were inspired by the newly formed Mount Vernon Ladies Association, which in 1859 bought the old George Washington estate, restored it, and still run it today.

The new association published an “appeal to the people,” beginning: “The Monument of Gd.

Army Engineers Take Over as Construction Resumes

There things sat for the next several years. Finally, on August 2, 1876, Congress passed a law to resume construction. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was to complete the job, led by Lt. Col. Thomas Lincoln Casey. Casey already had experience in building things. During the Civil War, he had put up a string of forts in Maine, in case disputes with the British should lead to a military threat from Canada. Later, in the 1890s, he was in charge of the construction of the Library of Congress, which stands just behind the Capitol.

Before doing anything else, Casey had to strengthen the monument’s foundation, which had proven to be quite inadequate for the weight to be placed upon it. Part of the original gneiss material was removed and replaced with concrete. The whole was then reinforced further by more concrete, completely encasing the foundation in a massive apron shape. For a brief time, the cornerstone was visible again, before being covered over for good. And a few more gentlemen who should have known better broke off chips as souvenirs.

s for the shaft, Casey removed the inferior Know-Nothing stone, plus two more feet of Washington National Monument Society stone, which was weather-damaged. Casey could then start fresh at the 150-foot landing.

On August 7, 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes was on hand to dedicate a second cornerstone at the 150-foot level. This one had no time capsule. Despite occasional trouble with supplies, the monument now grew steadily over the next few years.

At the behest of George P. Marsh, a scholar and diplomat of the day, the planned height of the column was reduced from the original 600 feet. In a true Egyptian obelisk, the height is 10 times the width at the base. The base was 55 feet, 1½ inches wide, and the column’s eventual height under the new plan ended up at 555 feet, 51/8 inches. Also, the pyramidion, the pointed peak forming the last 10 percent of the monument, was made much steeper than in the original plan. Its height was now greater than its width, again as in a true obelisk.

On December 6, 1884, the Washington Monument was finished at last.

As a crowd watched from below, Casey and several other staff met at the top, aboard a wooden platform made up for the occasion. Casey himself put in place the eight-inch aluminum tip. At the time, aluminum was a rare and expensive metal because the technology of the day found it dif- ficult to extract the metal from its ore.

On February 21, 1885, another crowd attended the monument’s formal dedication. It would have been February 22, George Washington’s birthday, but because that day was a Sunday, the dedication was moved back one day.

And so the Washington Monument became one of the city’s premier symbols.

The Memorial would be built on the same spot L’Enfant identified in his city plan of 1792. On July 4th, 1848 President James K. Polk presided over the ceremonial groundbreaking. Abraham Lincoln then serving his first and only term as a Representative from Illinois was in attendance as well as Dolley Madison, widow of President James Madison, and Elizabeth Hamilton, widow of Alexander Hamilton.

Construction continued for several more years. On April 20, 1849, the foundation was finished, and the shaft itself had already passed the 10-foot level. By December 20, 1849, when work stopped for the winter, the shaft had reached over 50 feet, and a just-installed 70-horsepower steam engine was being used to hoist the stones to the top.

But the Society needed to raise more money. The society put collection boxes across the country—at government offices, hotels, fairs, churches, election sites, and the monument itself. It offered souvenirs, such as certificates signed by the President and other VIPs.

And, to save money, the society dropped the idea of a colonnade around the base of the obelisk.

The society had to reduce expenses whenever it could, almost to the point of cornercutting. One obvious example of this was the composition of the walls of the monument: they were not actually solid. The outer layer was made of marble and the inner layer of gneiss—but in-between, the builders filled the space with irregular gneiss rubble.

The 1934 Restoration Provides More Strength

In 1934, during the first restoration of the monument, this section was strengthened by having liquid cement poured in at the 150-foot level, letting gravity fill up the gaps down to ground level. The round holes, now plugged, may still be seen at that landing, where the cement was added.

As a further cost-cutting measure, the inner layer of gneiss was cut by hand, even though (more expensive) machine cutters were available. A glance at the old inner walls today will show that every available piece or broken segment was used—as opposed to the machine-cut rectangular blocks further up, which were cut to precision.

The marble the society used for the outer layer must have come from one of the lowest bidders. It proved to be what would later be called “alum marble” because it crumbled so easily.

Today, for example, the corners of the monument have long since been replaced by new, whiter marble up the first 10 feet or so, the old material being damaged by erosion–and more relic-hunters. There are also scattered replacements further up to 150 feet, after which no replacements were needed.

During the 2000 restoration, there were piles of old society marble taken down and stored behind the scenes. One could pick up a lump and crumble it like cheese.

Women’s Groups Step In and Help Keep Project Going

The Washington National Monument Society did the best it could on a shoestring budget. Despite later repairs, the basic structure was sound—indeed, it is still there today. In mid-December 1854, however, the society had to announce that work would cease. It had spent $230,000 and raised the column to 152 feet. In 1855, Congress debated appropriating $200,000 for the monument to get things started again, but in that year the society was taken over by the American Party, better known as the Know-Nothings. (When asked about their activities, they would reply, “I know nothing.”) The party was a brief successful nativist movement in the mid-1850s that did not like Catholics and thought that the Pope wanted to control America. Ironically, they sometimes called themselves Native Americans.

After Pope Pius IX donated a commemorative stone to the Washington Monument, the Know-Nothings bought up memberships for themselves in the society, at one dollar apiece. They then showed up for the next meeting and overwhelmingly voted in their own people as officers. The original society refused to recognize the results, and so for a time there were two societies meeting side-by-side in the same small room in the City Hall’s basement.

After this, almost no one wanted to contribute anything. The Know-Nothings ended up using rejected marble lying about the grounds and so added a total of three feet, three inches to the monument. The original society regained control in 1858.

In 1859, a little-known episode in the monument’s history showed that the nation’s women refused to sit on the sidelines.

Several women founded the Ladies Washington National Monument Society. The Ladies group was created in Chicago, sometime in September, appropriately enough at the Masonic National Convention. A Mrs. Finlay M. King of New York was elected the president, and Mrs. Anna M. Cosby of Washington, D.C., became the secretary.

All the officers, in fact, were women. Perhaps they were inspired by the newly formed Mount Vernon Ladies Association, which in 1859 bought the old George Washington estate, restored it, and still run it today.

The new association published an “appeal to the people,” beginning: “The Monument of GEORGE WASHINGTON remains unfinished in the capital of the Republic he founded. Do you revere his name and memory?” It added, “Shall we prove recreant to the obligations this imposed on us? We cannot believe such a thing possible.”

Collection efforts in Washington, D.C., began on George Washington’s birthday, February 22, 1860. The first reports of the results appeared in the local Daily National Intelligencer of March 5, 1860, on page 1, and it was apparent that the Ladies group was already in trouble: “From the Masons of this city, through Major B[enjamin] French, $9.41; Kirkwood’s Hotel, $6.81; Washington House, 67 cents; Willard’s Hotel, 66 cents; Clarendon House, 34 cents; National Hotel, 55 cents; Brown’s Hotel, 12 cents; United States, 55 cents. Total $18.80.”

The Ladies society was, in short, having as much trouble prying open American wallets as their male colleagues. The next notice was in the Intelligencer for December 4, 1860, page 1, and listed local collections from the presidential election, the one that elected Abraham Lincoln. The total collection in the Washington area was $154.46.

Nationwide collections were little better. For 1861, the national total was $298.33. The Civil War had begun by now, and people had other things to think about than the monument. Sometime in 1863, the Ladies Washington National Monument Society disbanded.

Army Engineers Take Over as Construction Resumes

There things sat for the next several years. Finally, on August 2, 1876, Congress passed a law to resume construction. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was to complete the job, led by Lt. Col. Thomas Lincoln Casey. Casey already had experience in building things. During the Civil War, he had put up a string of forts in Maine, in case disputes with the British should lead to a military threat from Canada. Later, in the 1890s, he was in charge of the construction of the Library of Congress, which stands just behind the Capitol.

Before doing anything else, Casey had to strengthen the monument’s foundation, which had proven to be quite inadequate for the weight to be placed upon it. Part of the original gneiss material was removed and replaced with concrete. The whole was then reinforced further by more concrete, completely encasing the foundation in a massive apron shape. For a brief time, the cornerstone was visible again, before being covered over for good. And a few more gentlemen who should have known better broke off chips as souvenirs.

s for the shaft, Casey removed the inferior Know-Nothing stone, plus two more feet of Washington National Monument Society stone, which was weather-damaged. Casey could then start fresh at the 150-foot landing.

On August 7, 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes was on hand to dedicate a second cornerstone at the 150-foot level. This one had no time capsule. Despite occasional trouble with supplies, the monument now grew steadily over the next few years.

At the behest of George P. Marsh, a scholar and diplomat of the day, the planned height of the column was reduced from the original 600 feet. In a true Egyptian obelisk, the height is 10 times the width at the base. The base was 55 feet, 1½ inches wide, and the column’s eventual height under the new plan ended up at 555 feet, 51/8 inches. Also, the pyramidion, the pointed peak forming the last 10 percent of the monument, was made much steeper than in the original plan. Its height was now greater than its width, again as in a true obelisk.

On December 6, 1884, the Washington Monument was finished at last.

As a crowd watched from below, Casey and several other staff met at the top, aboard a wooden platform made up for the occasion. Casey himself put in place the eight-inch aluminum tip. At the time, aluminum was a rare and expensive metal because the technology of the day found it dif- ficult to extract the metal from its ore.

On February 21, 1885, another crowd attended the monument’s formal dedication. It would have been February 22, George Washington’s birthday, but because that day was a Sunday, the dedication was moved back one day.

And so the Washington Monument became one of the city’s premier symbols.

1848 Groundbreaking

1849 – Foundation finished

Column rises to 50 feet

70 horsepower steam engine was installed to lift the stones into place

1854 work stopped due to lack of funds. Column rises to 152 feet.

Know Nothings take over.

1861 – the grounds around the Memorial are used for grazing cattle

1876 Army Corp of Engineers takes control.