Building the U.S. CAPITOL

After the location of the new U.S. capital was determined, two buildings needed to be built – one for Congress to meet in (“Congress House”) and the other a home for the President (“President’s House”).

(Congress House was renamed “Capitol” by Thomas Jefferson).

So the new government held a contest for designs, advertising the contest in papers in the United States and overseas.

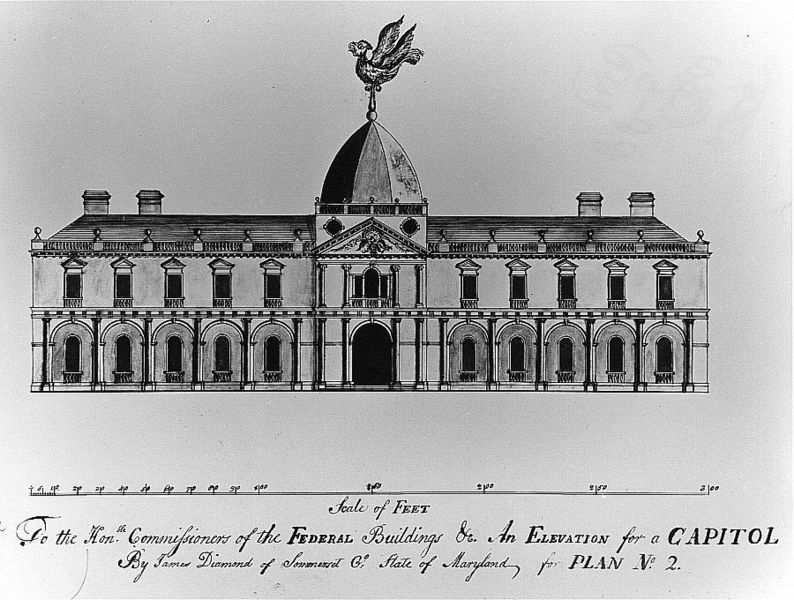

The competition for the new Congress House was disappointing. One design featured a gigantic bird, perched atop a cupola. George Washington complained:

“If none more elegant than these should appear…the exhibition of architecture will be a very dull one indeed.”

Reluctantly, Washington and Jefferson settled on the only plan from a professional architect, French-born Étienne (Stephen) Sulpice Hallet. But Hallet’s design was far from the classical architecture both men wanted for the new capitol.

Dr. William Thornton

Dr. William Thornton

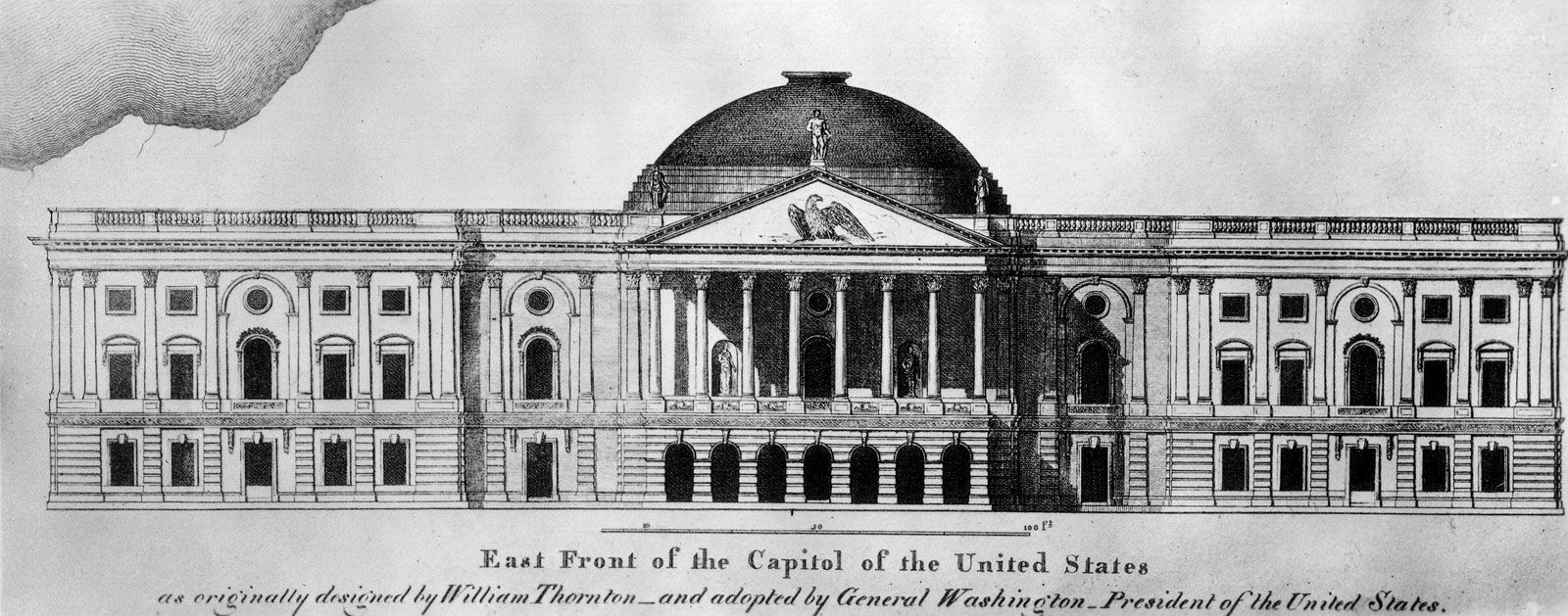

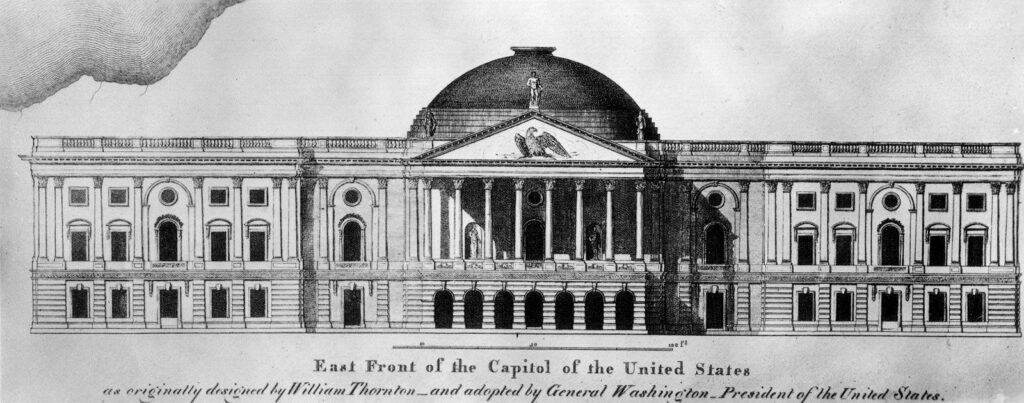

Thornton’s design was fully realized: he even imagined a series of statues incorporating a uniquely American iconography. Images including buffalo, elk and Indians would accompany figures from the ancient world, Hercules and Atlas: thus, emblems of the new nation’s wilderness and westward expansion would be wedded to classical symbolism. Thornton’s design overwhelmed George Washington with its “grandeur, simplicity, and beauty.”

By early February, Jefferson made it clear to federal commissioners that Thornton’s design enjoyed official favor, noting that it “so captivated the eyes and judgment of all as to leave no doubt you will prefer it.” On April 5, the commissioners informed Thornton that “the President has given his formal approbation of your plan.” Thornton’s reaction to the news is unrecorded. However, he quickly got down to work. Five days later, he submitted a minutely detailed report, outlining plans for everything from placement of windows and water closets to committee rooms and vestibules. )

hornton “succeeded, where others with practical experience had failed, because he grasped and was able to delineate the fundamental idea of the building,” writes C. M. Harris, an independent historian who is the editor of Thornton’s papers. “His knowledge of the ancient Roman writers allowed him to perceive the form and purpose, the political implications in Jefferson’s neoclassical concept of a modern capitol….[His plan] translated the Constitution into architectural form, creating a unique American building type.” Thornton, adds Harris, “redefined the sacred element of the temple, enshrining the lawmaking process upon which the success of the new republic depended, rather than any god or the authority of the state.”

The design, however brilliant, was not perfect. Although the Capitol’s exterior was magnificent, Thornton lacked a crucial skill: the architect’s ability to picture an interior in three dimensions. Thus, when professional builders examined his plans later in 1793, it became clear that its columns were spaced too widely to support architraves and that the staircases lacked sufficient headroom. The conference room’s interior colonnade, Jefferson objected, had “an ill effect to the eye, and will obstruct the view of the members: and if taken away, the ceiling is too wide to support itself.” Key sections of the building lacked sufficient light and air. The president’s office had no ventilation at all, while the Senate chamber was allotted only three windows. “Had Thornton’s plan been followed, the Senate would have suffocated,” says Allen.

The task of remedying the problems was assigned to none other than, as the commissioners put it, “poor Hallet,” whose own design had just been rejected. Hallet’s feelings, Washington wrote with some embarrassment, would have to be “sa[l]ved and soothed to prepare him for the prospect that the dr’s plan will be preferred to his.” Although Hallet did as he was bidden, he continued to lobby, unsuccessfully, for his own design to replace Thornton’s.

On September 18, 1793, a scene of nearly medieval pageantry unfolded in the new federal city as the moment came to lay the Capitol’s cornerstone. President Washington was accompanied by his brotherhood from local Masonic lodges. (The group’s origins lay in the workmen’s guilds of the Middle Ages, which by the 18th century had evolved into an elite fraternity that promoted the Enlightenment ideals of rationality and fellowship. During the Revolutionary War, Freemasonry had served as a powerful bonding force among officers of the Continental Army.) Washington and his compatriots marched resplendent in regalia of satin aprons, badges and sashes, accompanied by a military band and soldiers of the Alexandria Volunteer Artillery. One dignitary carried the Bible on a satin cushion, another a ceremonial sword. A local newspaper, the Columbia Mirror and Alexandria Gazette, reported “music playing, drums beating, colors flying, and spectators rejoicing.” Surveyors and federal officials, stonecutters and carpenters, along with prominent citizens, picked their way around potholes and tree stumps to Capitol Hill, along the route of what one day would be Pennsylvania Avenue. There, artillerymen unlimbered their guns and fired a cannonade that echoed resoundingly. Washington clambered into a trench where he laid the cornerstone. After another 15-round cannonade, “The whole company,” reported the Mirror and Gazette, feasted on “an ox of 500 pounds’ weight.”

The Capitol had been scheduled for completion by 1800. However, progress was hampered by incompetent management, contentious debates over the federal city’s future, labor disputes and shoddy construction. In 1795, as a result of slipshod work, the building’s foundation collapsed; not long afterward, a foreman absconded with $2,000 in workers’ salaries. Funding presented even bigger obstacles. The federal government initially had refused to appropriate public revenues for development of the capital city, insisting that money be raised through sales of municipal land, a system that failed repeatedly. Finally, in 1802, Congress grudgingly agreed to pay the project’s debt from the Treasury.

Despite the setbacks, the Capitol’s North Wing, housing the Senate’s semielliptical chamber, was completed, if only barely, in time for the arrival of Congress from Philadelphia in 1800. (For the time being, the House of Representatives would meet in the second-floor library.) When members of Congress entered the building that November to hear President John Adams proclaim the official installation of the government in Washington, D.C., the scent of newly cut lumber and fresh paint hung in the air.

It would take 33 years to complete the building that Thornton had begun to envision on Tortola. As the structure was altered and enlarged over time, Thornton’s name and his memory would be submerged beneath the work of others. The Capitol’s South Wing was completed by architect Benjamin Latrobe in 1811. The rotunda and portico were at last finished in 1826, under architect Charles Bulfinch. Major expansions, including new House and Senate wings, altered the Capitol in the 1850s and 1860s (when Bulfinch’s teacup-shaped dome also was replaced by the towering cast-iron dome punctuating the city’s skyline today.)

However, elements of Thornton’s design remain, including the original western facade of the wings, the stately Law Library Door at the southeast corner of the old North Wing and much of the eastern facade, now part of a corridor behind the East Front extension, erected between 1958 and 1961. The visitor center, plagued by delays and cost overruns, surveys the Capitol’s history, incorporating interactive exhibits and a live feed from House and Senate chambers when Congress is in session.

Thornton’s Capitol was the greatest design achievement of the early republic. “Thornton’s stroke of genius was to put wings on the Pantheon, and to make them the working parts of the building, and the Pantheon a ceremonial part,” says Allen. “He established for all time what the Capitol was to be. Everything that came later had to follow Thornton’s design.” His creation, Allen notes, would also inspire nearly every state capitol erected throughout the 19th century, most notably in North Carolina, Alabama and Mississippi. “By separating the wings, he also physically expressed the bicameral form of the government,” Allen adds. “He got everything right at once: the size, the degree of grandeur, the Anglo-American feel. It was the perfect recipe. Some of the alternative submissions had too much salt, so to speak, others too much pepper. Others were overbaked. Thornton’s was just right. It was a flash of genius.”

Thornton lived the rest of his life in his adopted city, which, with characteristic effusiveness, he compared to Constantinople, boasting, “We are approaching a state which will, I doubt not, be the envy of the world.” In 1794, President Washington appointed him to the three-man board of commissioners that oversaw the continuing development of the federal city. After the board was abolished in 1802, President Jefferson named him the head of the U.S. Patent Office, a position he held until his death, at age 68, in 1828. Thornton also designed several additional buildings that stand in Washington, including Octagon House (1798-1800), a couple of blocks from the White House and now a museum operated by the American Architectural Foundation, and Tudor Place (1816), a Georgetown mansion originally the home of the Peter family and now a museum as well.

But he was already one of the most celebrated figures of his time, a polymath and inventor. An acquaintance, jurist William Cranch, who would become chief justice of the D.C. federal court, said Thornton was “a little genius at everything.” Born on Tortola in 1759, he was sent at age 5 to be educated in England. After completing medical studies at Scotland’s University of Edinburgh in his 20s, Thornton began corresponding with the astronomer William Herschel. The young medical student’s connections also resulted in an introduction, in Paris, to Benjamin Franklin, the American ambassador to France. Thornton’s range of interests encompassed natural history, botany, mechanics, linguistics, architecture, government and—in another departure from the sober Quakers—horse racing. He had already helped to finance development of a steamboat and to design its boiler; invented a steam-operated gun; and proposed a “speaking organ to be worked by water or steam and to preach to the whole city.” He was the author of a treatise on comets. He also advocated ending bondage by resettling emancipated slaves in Africa, where Thornton envisioned a colony characterized by “the support of places of worship, of schools, and societies for the encouragement of science” and a legal system based on the Anglo-American model. (His ideas would ultimately influence the founding of Liberia.)

But he was already one of the most celebrated figures of his time, a polymath and inventor. An acquaintance, jurist William Cranch, who would become chief justice of the D.C. federal court, said Thornton was “a little genius at everything.” Born on Tortola in 1759, he was sent at age 5 to be educated in England. After completing medical studies at Scotland’s University of Edinburgh in his 20s, Thornton began corresponding with the astronomer William Herschel. The young medical student’s connections also resulted in an introduction, in Paris, to Benjamin Franklin, the American ambassador to France. Thornton’s range of interests encompassed natural history, botany, mechanics, linguistics, architecture, government and—in another departure from the sober Quakers—horse racing. He had already helped to finance development of a steamboat and to design its boiler; invented a steam-operated gun; and proposed a “speaking organ to be worked by water or steam and to preach to the whole city.” He was the author of a treatise on comets. He also advocated ending bondage by resettling emancipated slaves in Africa, where Thornton envisioned a colony characterized by “the support of places of worship, of schools, and societies for the encouragement of science” and a legal system based on the Anglo-American model. (His ideas would ultimately influence the founding of Liberia.)